Far-right activists, anti-democracy actors, and election deniers frequently use misleading terminology to advance patently false narratives of widespread election fraud in the United States. These groups use vague language, flawed statistics, and unsubstantiated claims to sow doubt about the integrity of our elections.

The language used by anti-democracy actors and election deniers is not simply inflammatory — it’s dangerous to our democracy. From talking about non-existent “dead voters” to attacking voting machines, it sows doubt about the accuracy and results of our elections.

That’s why below we’ve outlined the common debunked conspiracy theories and false claims perpetuated by election deniers and subverters, and explain what the common terminology used by election deniers actually means. In doing so, we hope to provide clarity for both the public and the media on what the vote counting and election certification process actually looks like and what the laws and practices that govern our elections actually are.

Below, we look at a few of the most common claims by election deniers, including:

Forensic Audit or Audit the Vote

Dead Voters, Voter Fraud, Illegal Voters

Attacks on Voting Machines

Calls for Hand Counts

Denying Certification

Upholding the integrity of our democratic institutions requires a commitment to truth, transparency, and respect for the rule of law. By understanding and accurately portraying these processes we can counteract the spread of misinformation and uphold the principles of democracy.

You can also read this full report on our Notion page.

“Forensic Audit” or “Audit the Vote”

What Election Deniers Claim

After Donald Trump lost the 2020 presidential election, election deniers insisted the election was somehow stolen and began a coordinated push for a “forensic audit” of the 2020 election.

Election deniers intentionally point to inaccurate or immaterial data to justify their false claims of election fraud, including party registration numbers, door-to-door canvasses, and findings from flawed databases like EagleAI.

Their efforts have not stopped. In Pennsylvania, for example, election deniers calling themselves Audit the Vote PA successfully petitioned county officials in Pennsylvania to recount the 2020 election two years after the election.

False Claim Language:

These are common ways that election deniers will falsely frame calls for a “forensic audit” or a “vote audit”.

“There were widespread irregularities in the election and probably outright fraud.”

“States must do an audit of the results to uncover the fraud.”

“We don’t know if we had a fair election because we don’t have the information we need to check.”

“They are suppressing evidence of voter fraud. Election officials who oppose an audit are hiding something.”

Examples from election deniers calling for forensic audits or vote audits:

The Reality

From poll-closing procedures, to machine and risk-limiting audits, audits and error checks are built into the process.

To find out more about the types of audits in your state see “50 State Post-Vote Guide: How We Count, Canvass, Certify, and Audit Our Elections: Risk-Liming Audits & Other Audits.” Informing Democracy, Jan 29, 2024.

Dead Voters, Voter Fraud, Illegal Voters, “Legal Votes”

What Election Deniers Claim

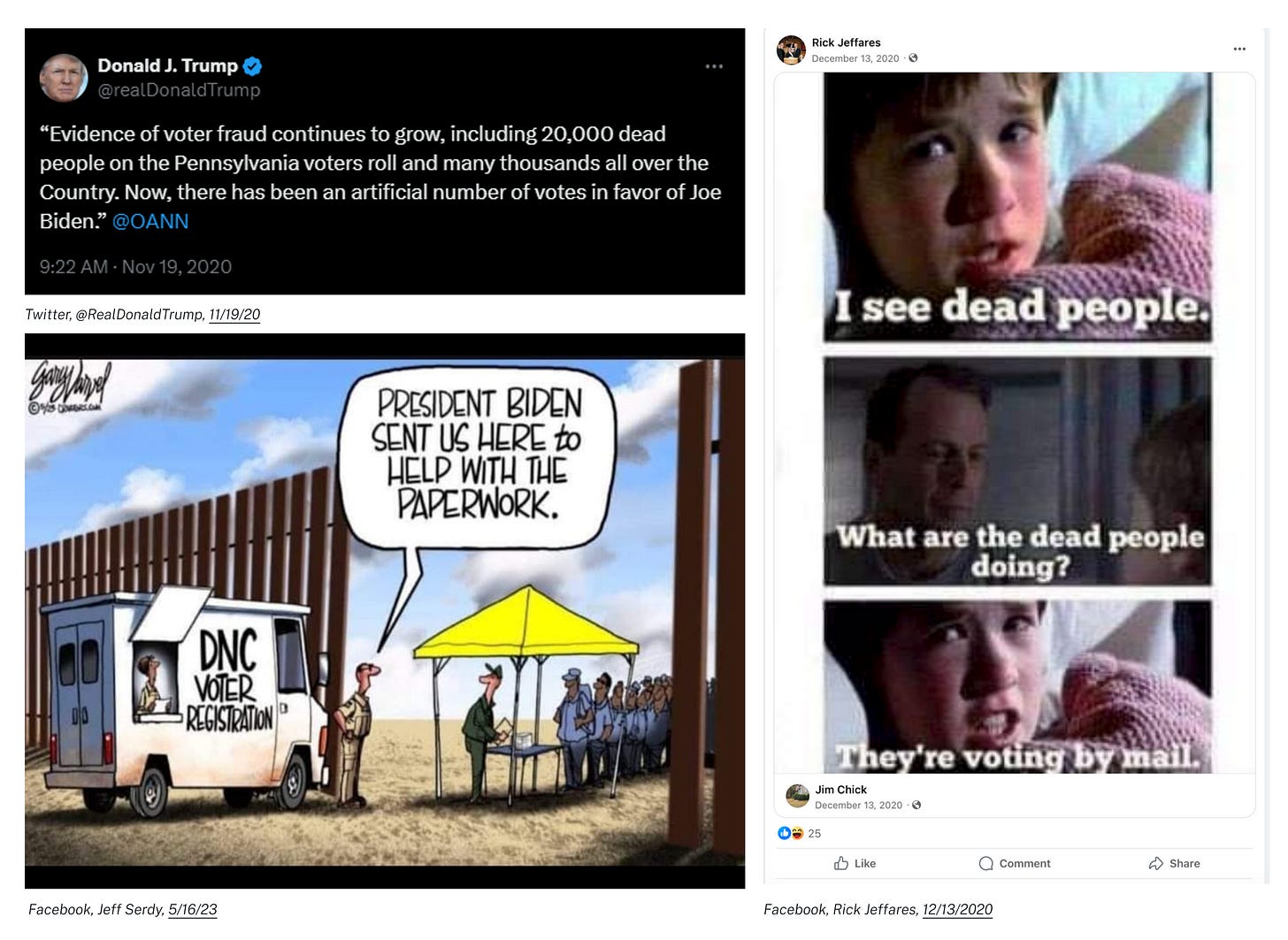

Election deniers falsely claim there is widespread voter fraud in our electoral system, largely driven by fraudulent votes in the names of dead voters and organized attempts to recruit undocumented immigrants to vote illegally. They largely attribute this fraud to the availability of mail-in voting. This often leads to calls to “count every legal vote.”

Following the 2020 election, election deniers claimed huge numbers of votes were cast on behalf of dead voters; subsequent investigations debunked these claims and those about widespread voting by noncitizens. Despite this reality, the Speaker of the House appeared with Donald Trump to tout a solution to this non-problem: a bill to prohibit noncitizens from voting.

False Claim Language:

Common ways that election deniers will claim voter fraud:

“Thousands of dead people voted in [swing state Donald Trump lost].”

“The dead vote for Democrats.”

“Millions of people are coming over the border illegally, registering to vote, and voting. Potentially hundreds of thousands of votes come from noncitizens voting, and we can’t stop it.”

“Count every legal vote.”

Examples from election deniers claiming voter fraud:

The Reality

There is very little voter fraud and check-in processes exist for all ballot types to ensure a voter’s name and information match their voter registration information before they are permitted to cast a ballot.

For vote-by-mail ballots, checking a voter’s eligibility is typically the first step taken by the elections office upon receipt of the ballot as a part of the pre-processing or pre-canvassing process.

See “50 State Post-Vote Guide: How We Count, Canvass, Certify, and Audit Our Elections: Pre-Canvassing.” Informing Democracy, Jan 29, 2024.

Attacks on Voting Machines

What Election Deniers Claim

Since the 2020 election, election deniers’ unfounded attacks on Dominion voting machines have snowballed into widespread distrust of any voting machine or tabulator.

As County Commissioner Rex Steninger — an election denier who pushed Elko County, Nevada to get rid of Dominion voting machines — said, “In my mind, logic tells me these machines can be tampered with.”

These suspicions led election deniers to try to gain unauthorized access to voting machines in places like Coffee County, Georgia to prove fraud.

False Claim Language:

Common ways that election deniers will attack voting machines:

“Voting machines are programmed to steal elections.”

“Voting machines are not certifiable.”

“Voting machines are secretly connected to the Internet and being hacked.”

“The tabulators on voting machines are rigged to flip votes.”

“We cannot trust machine counts, especially anything linked to Dominion software.”

“Machines can be used to count ballots multiple times.”

Examples from election deniers attacking voting machines:

The Reality

Logic and Accuracy Testing is a key part of the process before every election to ensure voting machines are working properly.

Additionally, post-election audit procedures in many states provide an additional check on the integrity of the results.

See “50 State Post-Vote Guide: How We Count, Canvass, Certify, and Audit Our Elections: Risk-Liming Audits & Other Audits.” Informing Democracy, Jan 29, 2024.

Calls for Hand Counts

What Election Deniers Claim

Building on their attacks against machine tabulation, election deniers are pushing for manual hand counts of every ballot, even though hand counting is much more prone to error and takes significantly longer than machine tabulation.

In Nevada, for example, election denier Jim Marchant travelled the state to lobby local officials to implement hand counts and successfully persuaded Esmerelda, Lyon, and Nye counties to show their support.

False Claim Language:

Common ways that election deniers call for hand counts:

“Because voting machines can’t be trusted, we should adopt a system that can’t be rigged — hand counting.”

"Hand counting ballots will restore voters’ faith in the system and bring in more transparency.”

“We need to get rid of machines related to elections entirely and return to all paper.”

The Reality

Full hand counts have repeatedly proven to be more resource intensive, less reliable and less secure than using optical scanning equipment to tally votes. For example, in Texas’ 2024 Republican Primary elections, Gillespie County chose to hand count results and had to correct counting errors in nearly all precincts.

Some states, however, provide for the partial hand-review of a sample of ballots as part of a risk-limiting or other audit process. These partial hand-counts or audit processes, unlike a full hand count, are a helpful double check on the system to ensure scanning equipment is functioning properly.

See “50 State Post-Vote Guide: How We Count, Canvass, Certify, and Audit Our Elections: Risk-Liming Audits & Other Audits.” Informing Democracy, Jan 29, 2024.

Vote “Dumps” and “Found” Votes

What Election Deniers Claim

As votes were counted during election night in 2020, Donald Trump’s lead in Wisconsin, Michigan, and Pennsylvania was cut significantly by the addition of votes from mail ballots. Election deniers began to claim these were “found” ballots, implying that they were fake.

This has morphed into a wider conspiracy about vote “dumps” that happen in the middle of the night to allegedly benefit Democrats.

False Claim Language:

Common language used by election deniers around the conspiracy of “vote dumping:”

“They dumped a bunch of votes overnight that allowed Biden to overtake Trump.”

“They keep ‘finding’ ballots in the middle of the night.”

“I’m not worried about what happens on Election Day. I’m worried about what happens at 3:00 a.m. on election night.”

“That van is delivering late votes for the ballot dump later.”

“They’re waiting to figure out how many votes they need to set up the ‘voter dump.’”

Examples from election deniers touting conspiracy theories about “vote dumping:”

The Reality

There are many steps to counting vote-by-mail ballots. Ballots must be checked in and voter eligibility confirmed. Ballots must also be opened, flattened, and run through optical scanning equipment before votes are tallied and results eventually released. See “50 State Post-Vote Guide: How We Count, Canvass, Certify, and Audit Our Elections: Pre-Canvassing.” Informing Democracy, Jan 29, 2024.

Therefore, in order to ensure results come in in a timely fashion after Election Day, many states start this counting process — called pre-processing or pre-canvassing — well before Election Day. However, to ensure the security of the vote and that voter’s decisions are not influenced mid-election, no results may be released until after polls close on Election Day.

The large batch of votes released just after polls close, therefore, reflects the vote totals from these vote-by-mail ballots that were preprocessed on or before Election Day.

Election Day votes, on the other hand, tend to come in on a precinct-by-precinct basis at different times after polls close. This variation can be affected by everything from how long the lines are to vote at the end of the day, to how big the voting location is — all of which can affect how long the various poll-closing procedures take. The timing is also dependent on the number of write-in, provisional, and challenged ballots that a location might be dealing with. Depending on the voting machine type used, there might also be a backlog of ballots that were cast, but not fed through tabulators, which can also add to the time needed after polls close to complete the count and release Election Day results.

In some cases, a delay in results being released can be a sign of some kind of malfunction at a polling location, such as was seen in Maricopa County, AZ in 2022 when tabulators were initially unable to read some ballots. Luckily, election officials are well-trained in troubleshooting errors and in backup procedures to ensure the integrity of both voting and counting. For example, in this case in Maricopa County all paper ballots were kept in secure containers until they could be tabulated.

Denying Certification

What Election Deniers Claim

Since 2020, there has been a troubling and growing trend of officials refusing to certify election results. These election deniers, who are actively sabotaging the democratic process, cite their belief the election was somehow stolen, unfair, or flawed.

Local officials have voted against certifying recent election results in Arizona, Georgia, Nevada, and Pennsylvania. In Arizona, Cochise County Supervisors Peggy Judd and Tom Crosby are facing felony charges of conspiracy and interference with an election officer for their refusal to certify the 2022 general election before the state’s deadline.

False Claim Language:

Common language used by election deniers refusing to certify election results:

“I’m not going to sign off on a stolen election.”

“We aren’t going to just rubber stamp this election with so many questions about its legitimacy.”

“I’m confident we ran a clean election but I don’t trust [major metro area’s] election.”

“Mail-in ballots are unconstitutional so this entire election has to be redone.”

“This is a political statement.”

Examples from election deniers refusing to certify the results of an election:

The Reality

Certification is complicated, but typically involves well defined, non-discretionary procedures to review and aggregate results. The Election Assistance Commission’s definition of certification is "a written statement attesting that the election results are a true and accurate accounting of all votes cast in a particular election." However, the process can vary from state to state and might include either a signed statement or some kind of on-the-record vote. See “50 State Post-Vote Guide: How We Count, Canvass, Certify, and Audit Our Elections: Local Canvass & Certification; State Canvass & Certification.” Informing Democracy, Jan 29, 2024.

Sometimes the law does permit officials to “correct obvious errors” or send the canvass results back to a more local level of officials for their corrections. See e.g. Me. Rev. Stat. tit. 21-A, § 711; Fla. Stat. Ann. § 102.111 (2); N.D. Cent. Code, §16.1-15-37.

However, certification is not a place to attempt to refute the outcome of the election and there is typically no power to simply “deny” certification. Rather, if there are genuine concerns about the integrity or finality of the results, then recounts, audits, and election contests are written into election law and are the places to look for a resolution.